The future of German agriculture – A task for society as a whole

“German Commission on the Future of Agriculture” (“Zukunftskommission Landwirtschaft”) presented its final report to Chancellor Angela Merkel on July 6, 2021. Various stakeholders unanimously state their commitment to strengthen efforts of environmental and climate action and to improve animal welfare. The Commission stipulates that for the successful transition to a more sustainable agricultural production, economic viability is an indispensable prerequisite. Farmers can only provide environmental services if the farms can secure a sufficient income. Stakeholders also agreed that the transition is a task for the whole of society and that politics needs to provide a conducive policy environment to enable change.

Germany as a trailblazer for future-oriented thinking?

Germany already has developed standards that are considerably higher than the EU average regarding various sectors, particularly in the field of animal welfare: It is the world’s first country to ban the culling of male chicks (offspring of laying hens) by the end of 2021. This follows the ban on castrating piglets without anesthesia at the start of 2021. Almost in passing, a leading discounter recently announced that it would only sell meat that was produced in line with higher animal welfare standards by 2023. These new trends ask for quite significant adjustments in livestock keeping. Therefore, they raise the question, if the legal requirements (e.g. construction law, clean air act) will be adjusted to support the modifications needed for higher animal welfare and if there will be enough incentive for livestock farmers in Germany to make it happen.

A diverse committee acknowledging various interests

The final report of the Commission on the Future of Agriculture, a toughly negotiated agreement, runs in a similar vein and summarizes pragmatic concessions from different interest groups for the sake of the greater good. Thirty-one committee members representing agriculture, trade, animal welfare, consumer organizations, environmental protection and science, were asked to develop a shared vision, recommendations and guidelines for a sustainable and future-oriented German agriculture. Established in September 2020 by Chancellor Angela Merkel the committee met regulary. Ideas how to reduce external costs and to preserve nature for future generations while at the same time maintaining food security in Germany were exchanged. The report presents pathways for sustainable agricultural production systems that consider economic, ecological, and social objectives as well as animal welfare.

Transformation needs support from the society as a whole

Traditionally, perspectives on controversial topics, such as animal welfare standards and the economic compensation for farmers who carry out additional conservation practices, differ widely between agriculture and nature conservation. Considering the partially hardened positions of the two professions, it is commendable that the Commission on the future of agriculture reached a consensus under a constructively supporting chairmanship. Guiding principle and starting point for the committee’s work was the notion that environmental efforts must translate into economic success and societal recognition. Support of the whole society is necessary for a successful transformation. Putting responsibility only on farmers will not do the job. More likely, it will lead to the exhaustion of families and abandonment of farms.

Key outcomes

The 190-page document combining the diverse expertise of the committee members is worth a read. It features familiar ideas as well as progressive thinking.

Most significant outcomes from a farmer’s perspective are the following:

- The German agri-food sector continues to walk the path towards a more sustainable future.

- Agriculture alone cannot bear the massive cost necessary for the transformation process.

- Both, companies and society need to invest in German agriculture.

- Only sufficient income will secure the future viability of farms and motivate new agricultural practitioners.

- A shift of agricultural production abroad (leakage effects) through unbalanced (and underfinanced) regulations needs to be prevented.

- The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) should be further developed and (together with national funding) support the transformation while securing the urgently needed planning and investment certainty for farmers.

- New breeding techniques should be used to develop plant varieties adapted to challenges posed by climate change and pests.

- Requirements for animal welfare should be (financially) supported to secure the perspective for high-quality livestock farming in Germany.

- Research and innovation should provide the knowledge base for resource-, animal-, and climate-friendly practices.

- Digitalization offers the potential to reduce the use of fertilizer and plant protection products through precision agriculture.

A Common Agricultural Policy

CAP support will play a key role in financing and managing the transition to a sustainable food system in Germany. Provided that farms can operate sufficiently competitive, CAP support has to enable farmers to contribute to additional ecological and social achievements. The uphill struggle in the course of the EU trialogue negotiations on the CAP 2023-2027 has shown how hardened positions of different interest groups can endanger the necessary financial support for farmers. At the end of June 2021 a compromise was reached, just in time to not fail the millions of European farmers relying on the CAP’s financial income support.

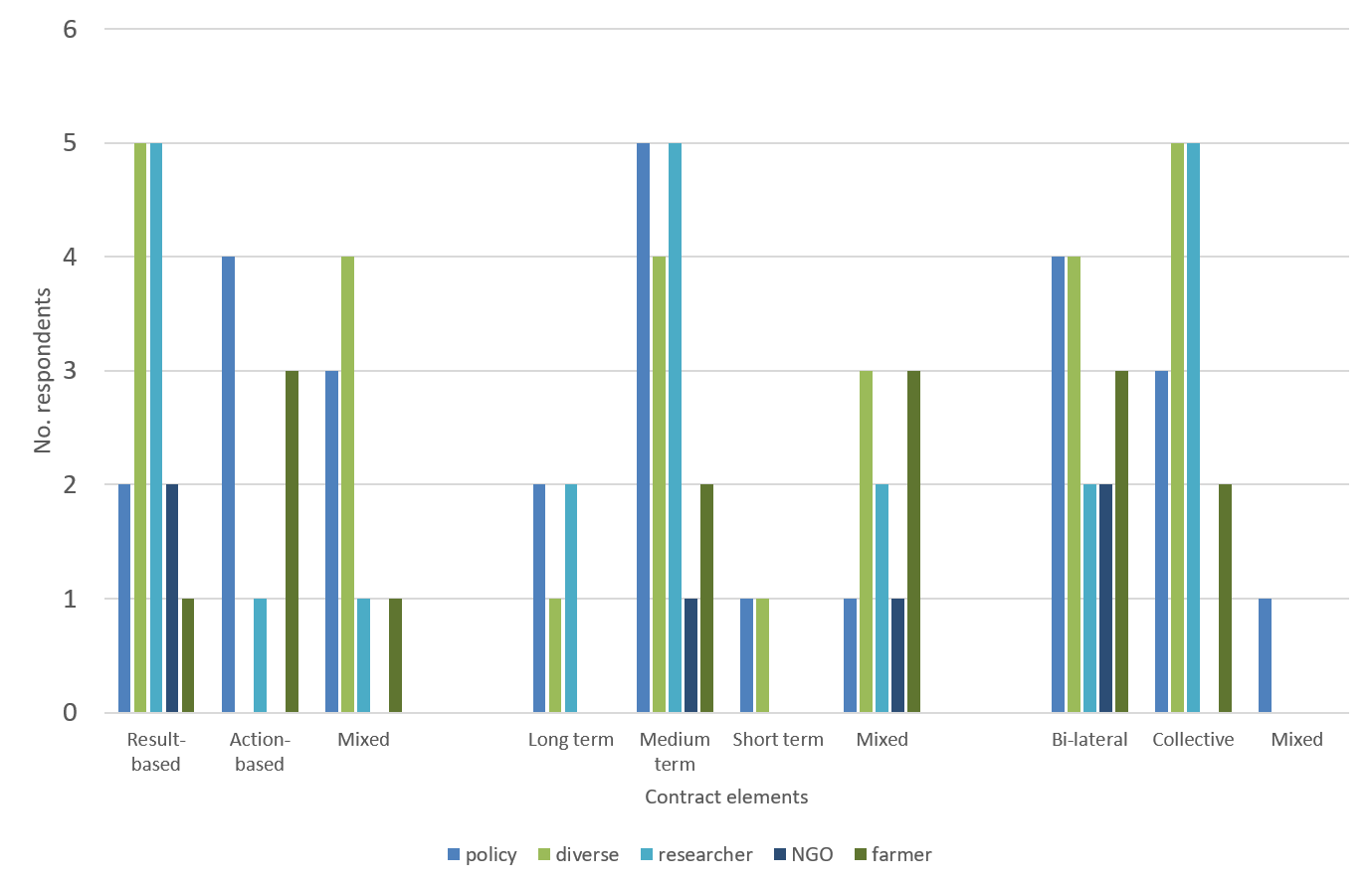

Cooperation is the key to success

In the long term, the “Zukunftskommission Landwirtschaft” suggests for Germany that area-based direct payments should be gradually converted into payments supporting specific measures to reach societal goals (such as clean water or sustaining biodiversity) within the next two CAP funding periods. The committee emphasizes that during the transition process, farmers should not suffer a net loss to their income. Furthermore, instead of regulation, cooperation should be fostered to motivate farmers to implement ecologically effective measures on their farms. To increase the effectiveness of agri-environment-climate measures (AECM) a collective implementation (e.g. Dutch collective model) is specifically mentioned as being a promising solution due to its landscape scale approach. The report also emphasizes the necessity for consumers to accept fair prices for agricultural products. They should integrate the higher production costs, to maintain the profitability of agricultural enterprises.

A blueprint for a greener future?

Although not a legally binding document, policy makers will hardly be able to ignore the report. In the eyes of the committee members, the recommendations of the commission should serve as a blueprint for policy innovation. The next German government is likely to be judged according to its efforts regarding the support of the transformation process. The recommendations have the potential to get politics moving and motivate society to live up to the commitment to make this ambitious vision come true.