To Innovate or not to Innovate? – A Danish Study on Conservation Grazing Schemes

A study on different options to improve a scheme on conservation grazing revealed that Danish farmers are not hugely keen on adopting innovative contractual approaches. Even though many of the Danish farmers feel the need to increase the ecological impact of the measures, they argue that this could be achieved by improving the existing schemes.

How relevant are findings from the Innovation Lab to the Danish farming community?

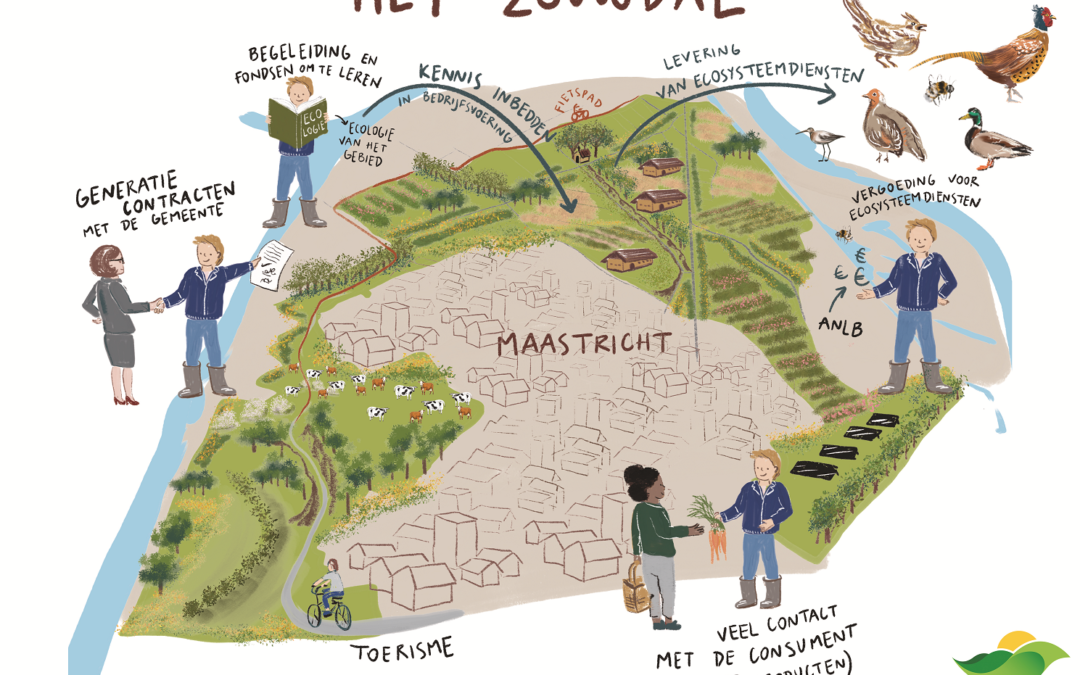

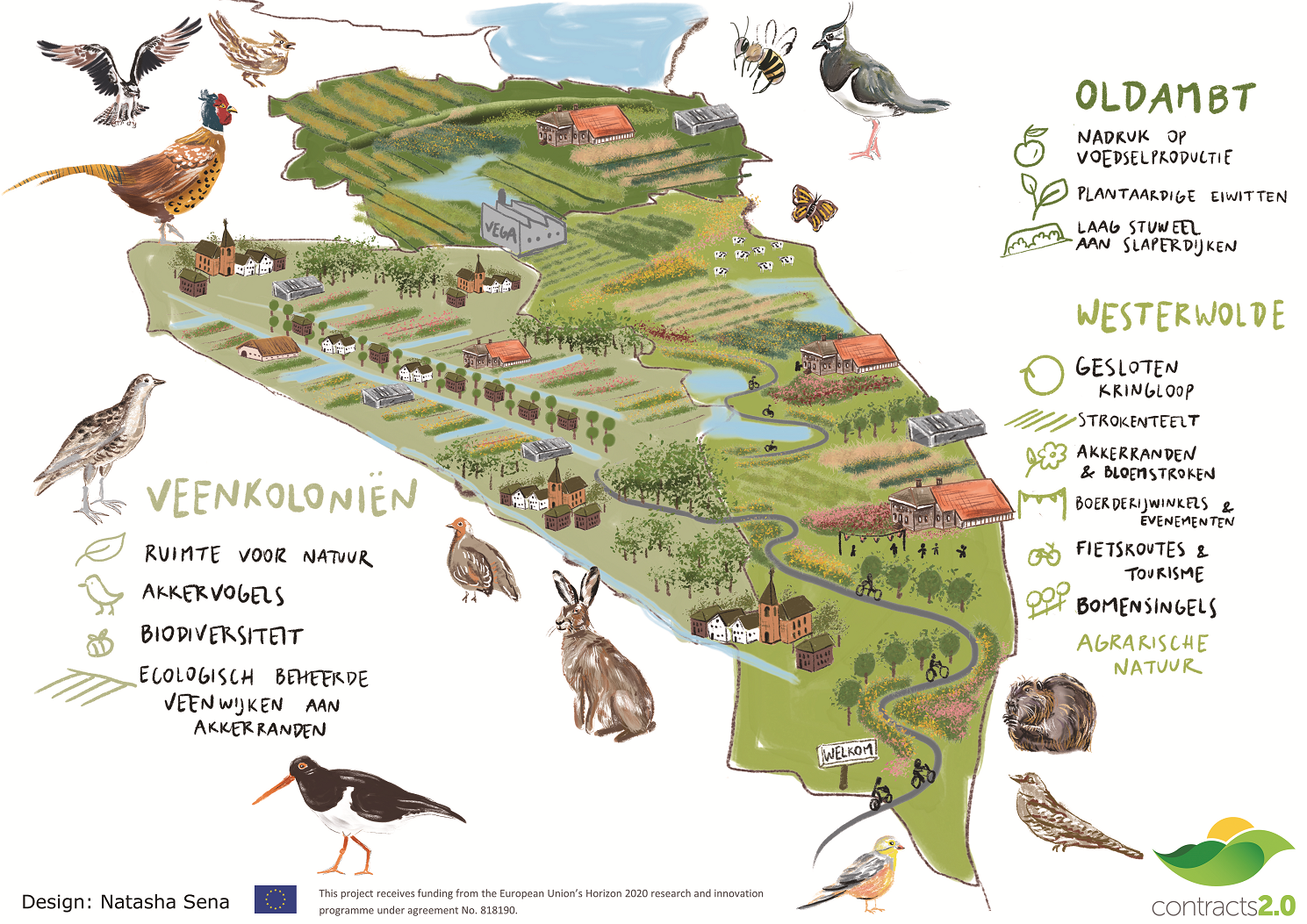

Contracts2.0 aims to develop innovative contracts between farmers or land managers and other public or private bodies, which help to strengthen the implementation of agri-environmental measures in agriculture. This is done mainly in the Contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More Innovation Labs (CIL), which have a regional or local base. In our Danish case, innovative solutions for contracts on conservation grazing have been developed on the island of Bornholm, which covers 1.3 % of the Danish agricultural area and is the home of 1.2 % of the Danish farmers.

In our CIL, the farmers of Bornholm expressed interest in the integration of innovative components to boost the impact of the existing measures. However, are the novel solutions developed in a specific region also applicable in national contexts? To check the national applicability of the innovative approaches, we initiated a survey addressing affected farmers all over Denmark. 370 farmers, a little less than 10 % of all farmers currently participating in a scheme on conservation grazing, provided answers.

The Top 4 preferred options are old acquaintances

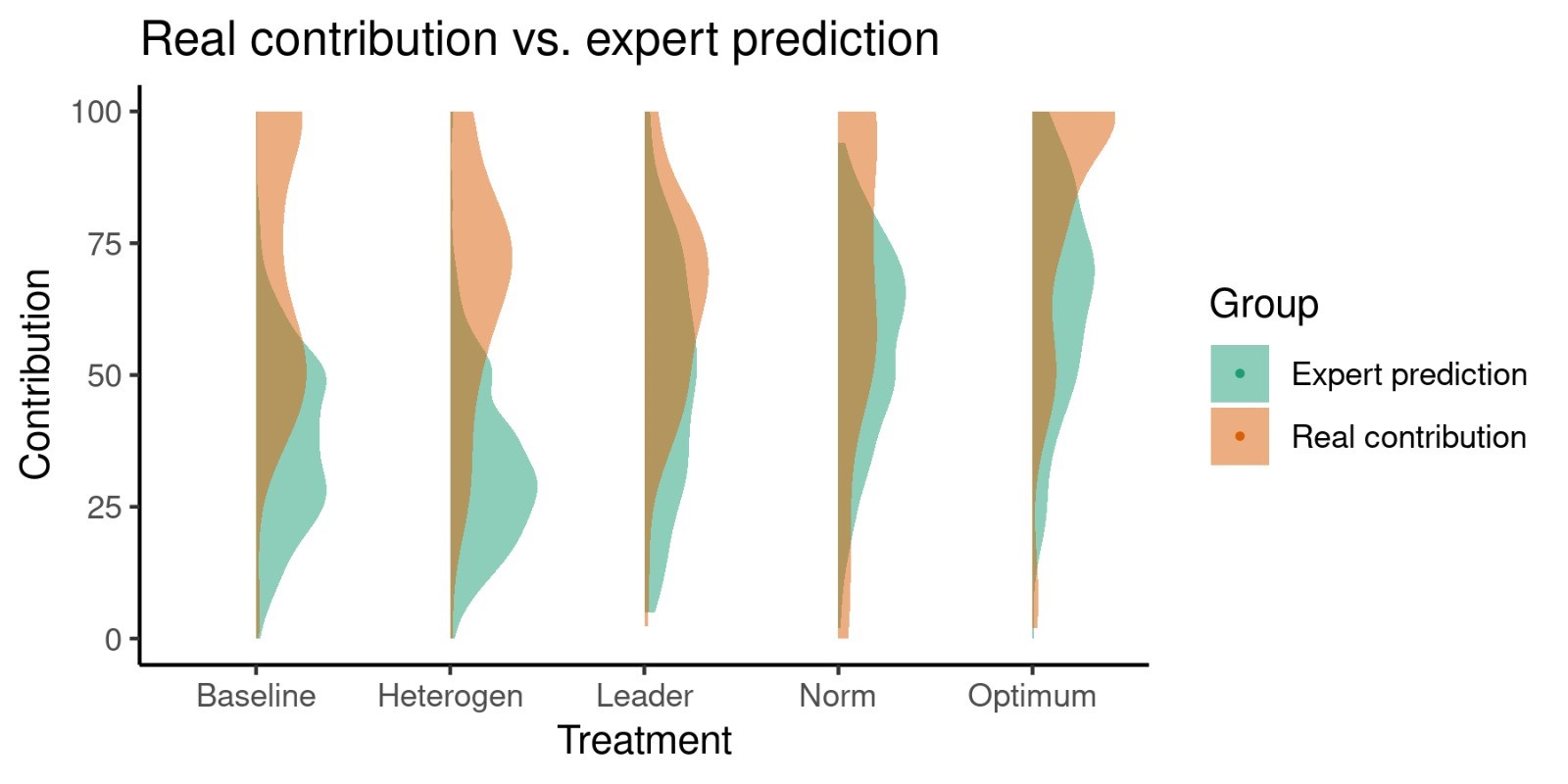

The question we considered as the most important, dealt with potential options to provide farmers with additional payments for additional efforts. Six different options were listed, and each farmer could choose up to three favoured options.

The option that farmers point to as most interesting actually already existed earlier (albeit to a limited extent) in older versions of the Danish scheme for the management of grassland and natural areas. More than four out of ten farmers indicate that they would be interested in obtaining additional payment for small areas and areas with difficult access, i.e. areas with relatively high management costs.

The second most popular option is to get extra payments for more specific requirements. Again, this is an option previously available in the Danish scheme with differentiation according to, for example, the use of fertilisation and grazing pressure at different levels.

Thirdly, a little more than one in three farmers is interested in obtaining additional pay out for following a management plan for the contracted area. Today, management plans are already a reality for a number of farmers managing publicly owned land, but the support scheme is currently not directly linked to the plan. The most frequent model in these situations is that the authorities lease the land to the farmer and that the farmer holds the contracts on conservation grazing and gets the payment for this.

In fourth place is a bonus payment for maintaining areas of high nature value (HNV) according to the map of the Agricultural Agency. At present, aid is not differentiated according to the HNV-levels of the land, as the HNV feature is only used to determine whether land outside Natura 2000 areas is eligible for enrolment in conservation grazing schemes or not.

What about the rest?

Only slightly more than one farmer in five would opt for a scheme offering an additional payment when meeting certain nature quality indicators. Slightly fewer than one in five farmers would like to see a bonus payment for high local contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More coverage (agglomeration bonusis an additional payment to the providers of ecosystem services (ES) if an environmental outcome has been achieved at a larger spatial scale (e.g., beyond the field/ farm scale, within a predefined region/landscape or watershed). ... More). The latter has been tried for a period of time with a small additional payment of 10% for local coverage of more than half of the eligible area.

Additionally, two thirds of the farmers are interested in improving the management of grasslands in the conservation grazing scheme to improve or secure the nature content. Apparently half of these farmers are even interested in improving management without additional payments.

Conclusions from the Danish Survey

Three observations can be made from the results presented here. Firstly, none of the presented options alone would be attractive for the majority of farmers. Secondly, the contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More option featuring an individual management plan, developed in the Innovation Lab Bornholm, scores relatively high in the survey among the farmers from other parts of the country. Thirdly, the options with innovative elements, like results-based paymentsare an approach where farmers and land managers are paid for delivering environmental outcomes, for example for enhancing the presence of important grassland species. In these schemes, farmers determine the management required to ... More or collective implementation score relatively poor.

For further reference, see our survey results in the Graph below.

Bottom line…

…tweaking the existing schemes can bring about desired results in terms of conservation grassland management. Many farmers are generally interested in improving management to improve or secure the nature content of the grasslands under agreement. The Contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More Innovation Lab on Bornholm suggests integrating the innovative approaches in the implementation of nature protection management plans in the agri-environmental schemes on conservation grazing under the Common Agricultural Policy.

The survey which also covers farmers’ views on other issues of agri-environmental programs (e.g. checks/controls, advisory services) is reported in Andersen, E.: Landmændenes syn på tilsagn om pleje af græs- og naturarealer (original, in Danish). A reviewed English translation is available here.