A student project analysed an organic food value chain by interviewing stakeholders including production, processing and retailing as well as politics. The objective was to find out how relationships within value chains have to be build out to promote a sustainable value chain. The most important result was that cooperationSee collaboration. More at eye level between all stakeholders is necessary to strengthen biodiversity and ecosystem services in a sustainable organic value chain.

Organic farming has great potential to contribute to an environmentally sound and sustainable agricultural production. It integrates the objective of conserving natural resources into its core principles, and therefore has a variety of positive effects on the environment. It can also play a vital role in the efforts regarding climate protection and climate adaptation.

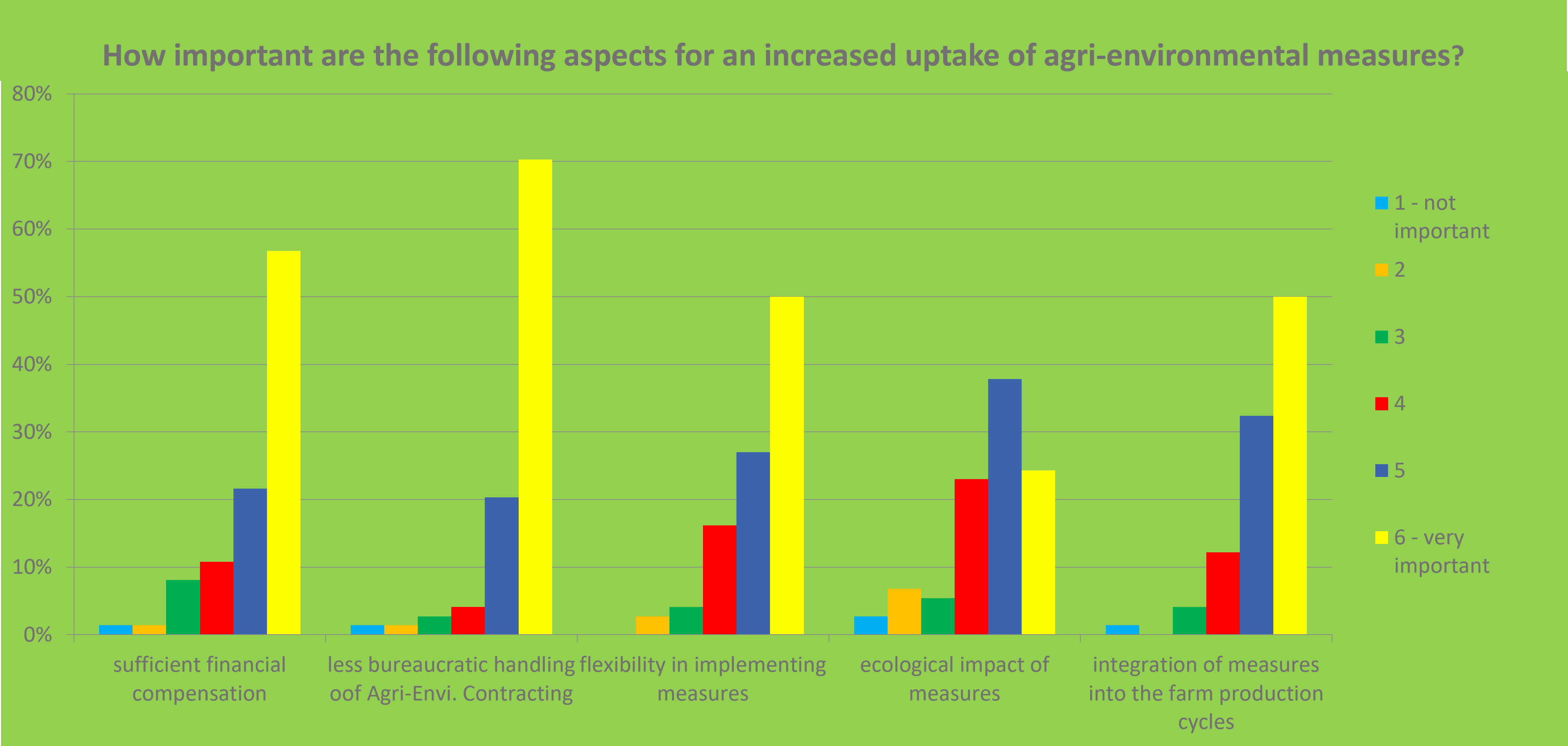

The HiPP Contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More Innovation Lab of Contracts2.0 focuses on services that can be achieved in organic value chains in addition to those already generated by requirements of organic farming associations. An innovative contract-based approach along organic food value chains could provide support or incentives for farmers to contribute to strengthening biodiversity and ecosystem services in addition to producing food, i.e. integrating them into sourcing and quality strategies within food production.

Exploring the Potential of Sustainable Organic Value Chains

As part of a study project in parallel to the work in the HiPP CIL, students from Leibniz University Hannover, Germany, discussed ways of making organic value chains more sustainable. The students conducted a case study in which stakeholders along the value chain of an organic grain mill were interviewed on the topics of sustainability, biodiversity and ecosystem services. The stakeholders included farmers, mill managers, retail partners as well as staff of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and Ministry of the Environment of Lower Saxony. Within these interviews, the following subjects were discussed:

- Strengths and weaknesses of a sustainable organic grain value chain,

- Framework conditions to set up a more sustainable value chain from the perspective of the various stakeholders,

- A theoretical cooperationSee collaboration. More model which describes the mutual demands and commitments of the stakeholders.

The following sections focus on the description of the cooperationSee collaboration. More model and the necessary framework conditions that underpin this model.

What are the Necessary Framework Conditions?

Important framework conditions for creating a sustainable organic value chain promoting biodiversity and ecosystem services, are communication, trust and cooperationSee collaboration. More of all internal and external stakeholders. This includes information exchange, knowledge exchange, the communication of ecological values, and education.

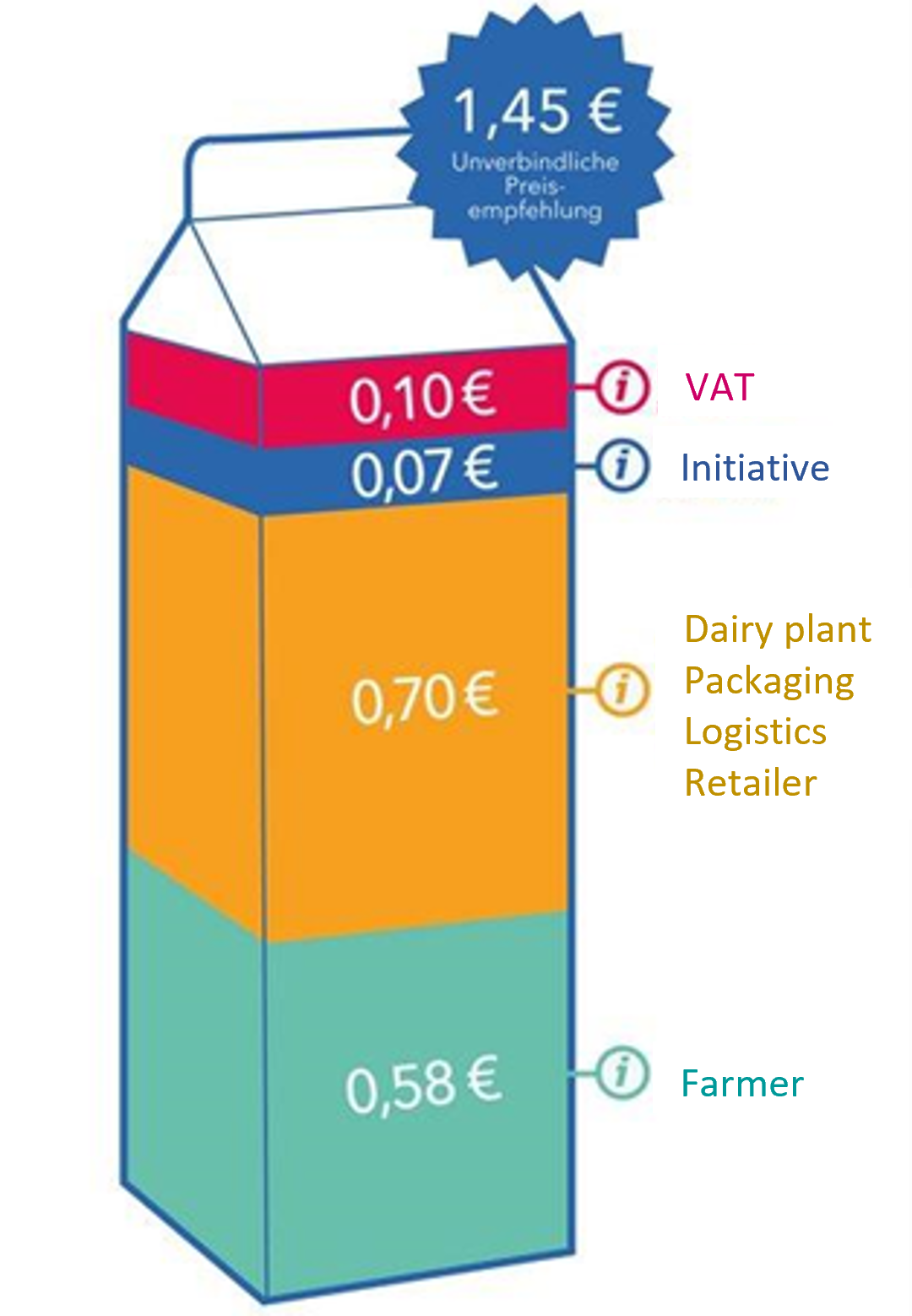

Examples are fair prices and price transparency. For example, the studied grain mill introduced a so-called “base price model” for long-term pricing to counteract market fluctuations. This guarantees farmers greater security in the sale of their products.

Another point that was addressed is the buying behaviour and the appreciation of organic products by consumers. On the one hand, consumers must be convinced and informed that organic or regional products could be more expensive and it is worth paying this extra effort. On the other hand, farmers must be made aware of the added value of sustainable projects, both ecologically and economically.

Last but not least, political funding and financing plays an important role. This funding can support pilot projects testing pathways to sustainable organic value chains. An example of such a promotion of regional initiatives is the producer association “Kostbares Südniedersachsen”. Here, public funding has been successively discontinued and replaced by retailers’ initiatives. This is a rare example, because until now such approaches have been financed predominantly by food processors from their own funds.

In addition, policies contribute to the adherence to the principles of a sustainable value chain and production security for the various stakeholders through guidelines and operation standards, such as the “Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supple Chains”.

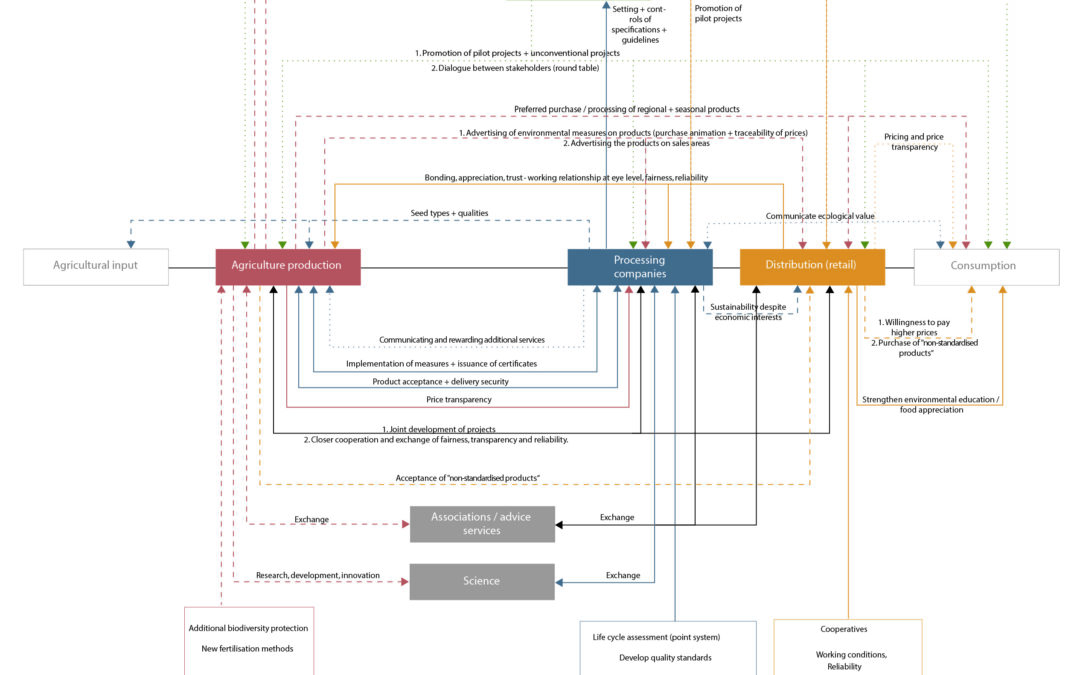

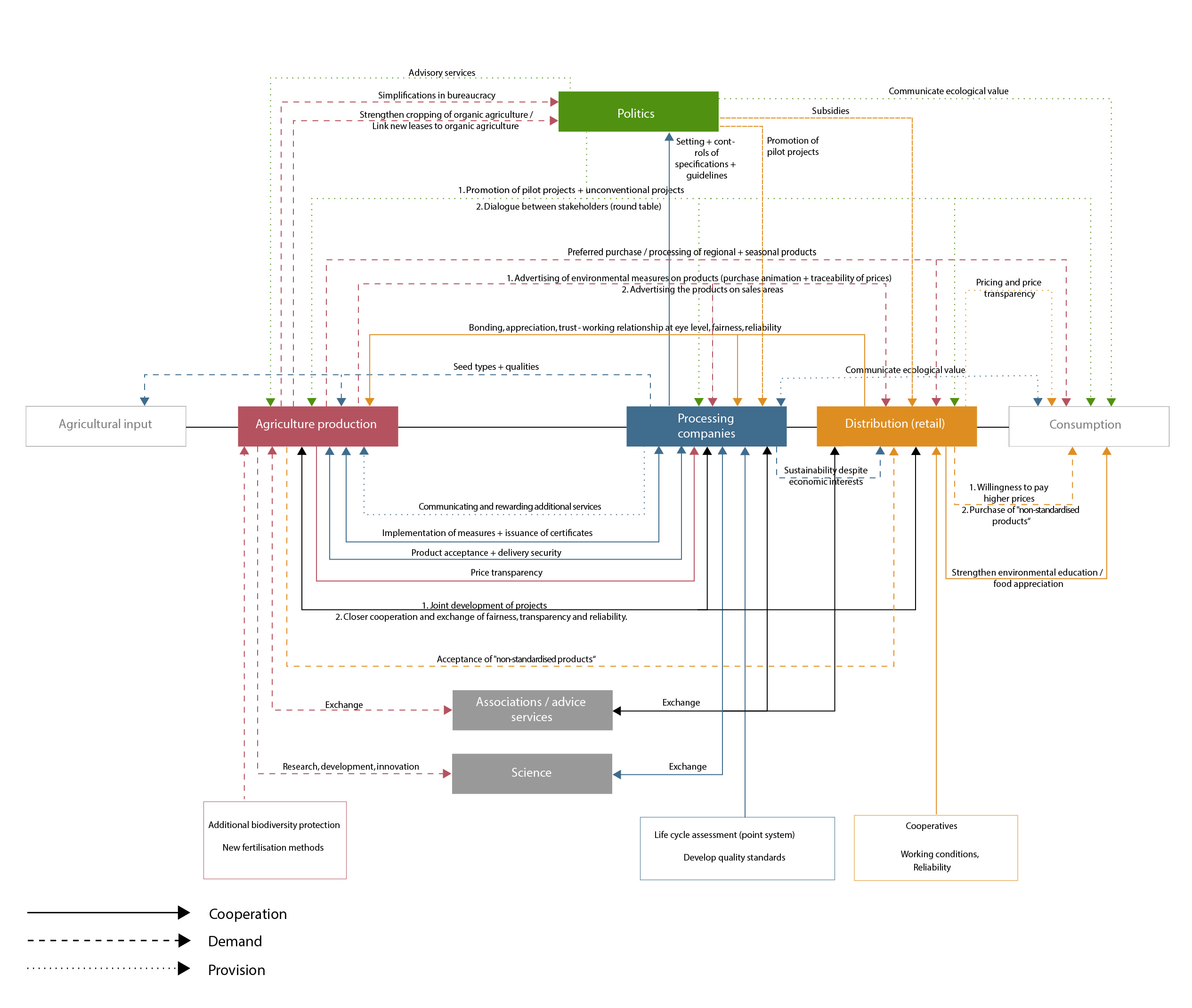

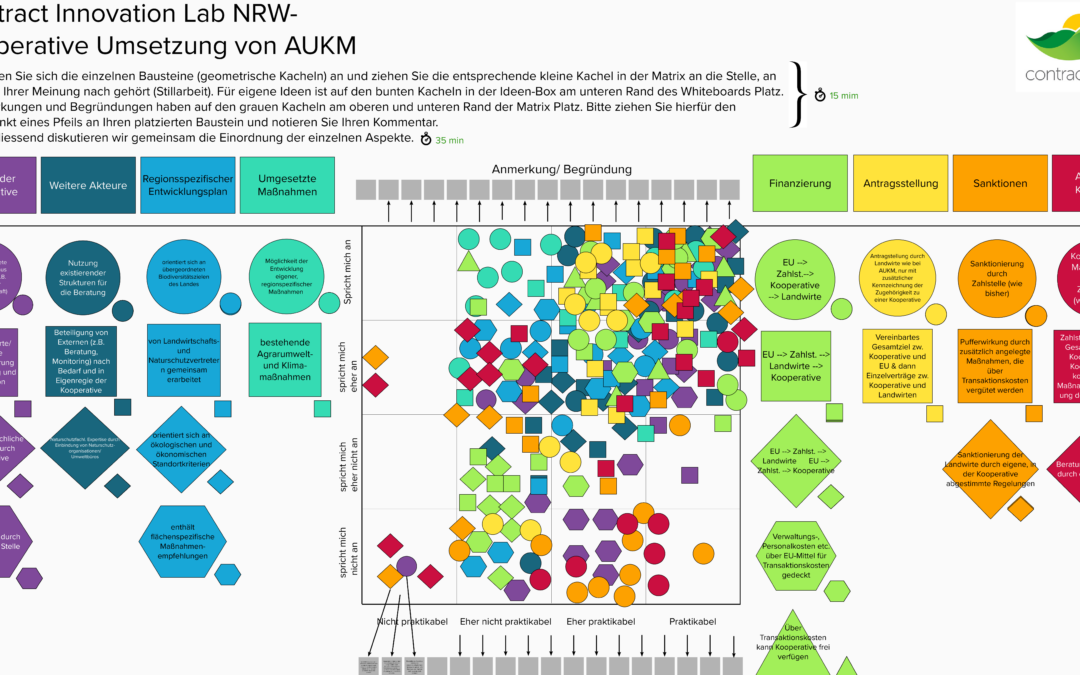

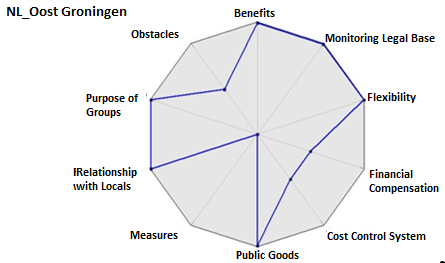

Developing a Cooperation Model to Identify Needs and Commitments of the Stakeholders

The outputs generated through the interviews were visualized in a cooperationSee collaboration. More model. The following figure shows the complex interlinkages between the stakeholders within this cooperationSee collaboration. More model of the sustainable grain value chain. The individual needs and commitments of the stakeholders are shown and describe the most important topics of cooperationSee collaboration. More among the various stakeholders.

The model also shows that the stakeholders mainly share the same beliefs. An example is the desire for closer cooperationSee collaboration. More and the development of joint projects as well as a transparent, reliable and trustworthy communication.